Archive

Some pair programming benefits may be mathematical artefacts

Many claims are made about the advantages of pair programming. The claim that the performance of pairs is better than the performance of individuals may actually be the result of the mathematical consequences of two people working together, rather than working independently (at least for some tasks).

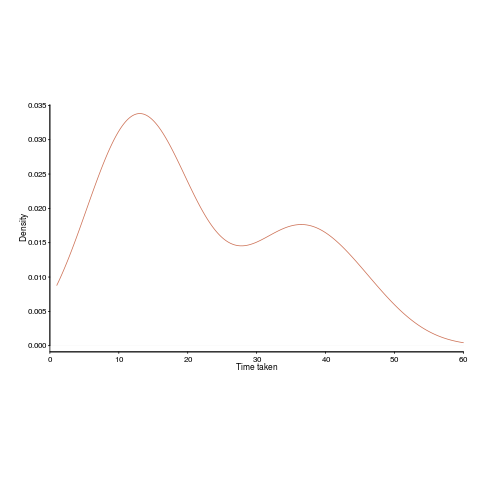

Let’s say that individuals have to find a fault in code, and then fix it. Some people will find the fault and then its fix much more quickly than others. The data for the following analysis comes from the report Experimental results on software debugging (late Rome period), via Lutz Prechelt and shows the density of the time taken by each developer to find and fix a fault in a short Fortran program.

Fixing faults is different from many other development tasks in that if often requires a specific insight to spot the mistake; once found, the fixing task tends to be trivial.

The mean time taken, for task t1, is 22.2 minutes (standard deviation 13).

How long might pairs of developers have taken to solve the same problem. We can take the existing data, create pairs, and estimate (based on individual developer time) how long the pair might take (code+data).

Averaging over every pair of 17 individuals would take too much compute time, so I used bootstrapping. Assuming the time taken by a pair was the shortest time taken by the two of them, when working individually, sampling without replacement produces a mean of 14.9 minutes (sd 1.4) (sampling with replacement is complicated…).

By switching to pairs we appear to have reduced the average time taken by 30%. However, the apparent saving is nothing more than the mathematical consequence of removing larger values from the sample.

The larger the variability of individuals, the larger the apparent saving from working in pairs.

When working as a pair, there will be some communication overhead (unless one is much faster and ignores the other developer), so the saving will be slightly less.

If the performance of a pair was the mean of their individual times, then pairing would not change the mean performance, compared to working alone. The performance of a pair has to be less than the mean of the performance of the two individuals, for pairs to show an improved performance.

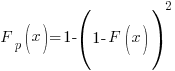

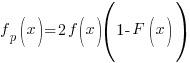

There is an analytic solution for the distribution of the minimum of two values drawn from the same distribution. If  is a probability density function and

is a probability density function and  the corresponding cumulative distribution function, then the corresponding functions for the minimum of a pair of values drawn from this distribution is given by:

the corresponding cumulative distribution function, then the corresponding functions for the minimum of a pair of values drawn from this distribution is given by:  and

and  .

.

The presence of two peaks in the above plot means the data is not going to be described by a single distribution. So, the above formula look interesting but are not useful (in this case).

When pairs of values are drawn from a Normal distribution, a rough calculation suggests that the mean is shifted down by approximately half the standard deviation.

Power law of practice in software implementation

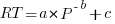

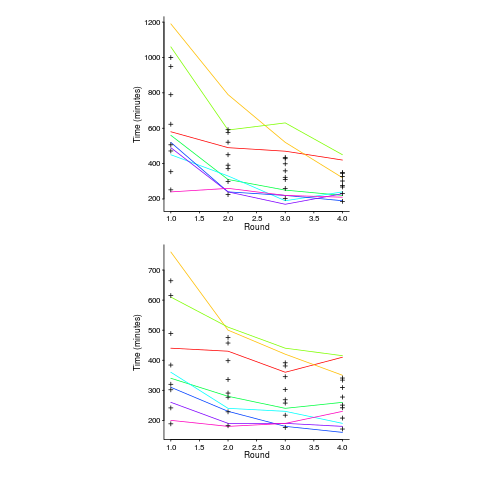

People get better with practice. The power law of practice specifies  , where:

, where:  is the response time,

is the response time,  the amount of practice and

the amount of practice and  ,

,  and

and  are constants. However, sometimes an exponential equation is a better fit for to the data:

are constants. However, sometimes an exponential equation is a better fit for to the data:  . There are theoretical reasons for liking a power law (e.g., it can be derived from the chunking of information), but it is difficult to argue with the exponential fitting so much data better than a power law.

. There are theoretical reasons for liking a power law (e.g., it can be derived from the chunking of information), but it is difficult to argue with the exponential fitting so much data better than a power law.

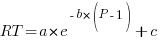

The plot below, from a study by Alteneder, shows the time taken to solve the same jig-saw puzzle, for 35 trials (red); followed by a two week pause and another 35 trials (in blue; if anybody else wants to try this, a dedicated weekend should be long enough to complete over 20 trials). The lines are fitted power law and exponential equations (code+data). Can you tell which is which?

To find out if the same behavior occurs with software we need data on developers implementing the identical applications multiple times. I know of two experiments where the same application has been implemented multiple times by the same people, and where the data is available. Please let me know if you know of any others.

Zislis timed himself implementing 12 algorithms from the CACM collection in each of three languages, iterating four times (my copy came from the Purdue library, which as I write this is not listing the report). The large number of different programs implemented, coupled with the use of multiple languages, makes it difficult to separate out learning effects.

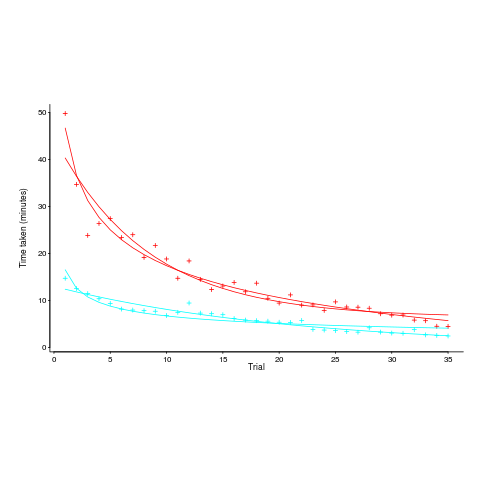

Lui and Chan ran an experiment where 24 developers (8 pairs {pair programming} and 8 singles) implemented the same application four times. The plot below shows the time taken to complete each implementation (singles top, pairs bottom, with black cross showing predictions made by a power law fit).

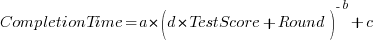

Different subjects start the experiment with different amounts of ability and past experience. Before starting, subjects took a multiple choice test of their knowledge. If we take the results of this test as a proxy for the ability/knowledge at the start of the experiment, then the power law equation becomes (a similar modification can be made to the exponential equation):

That is, the test score is treated as equivalent to performing some number of rounds of implementation). A power law is a better fit than exponential to this data (code+data); the fit captures the general shape, but misses lots of what look like important details.

The experiment was run over successive weekends. So there was opportunity for some forgetting to occur during the week days, and the amount forgotten will vary between people. It is easy to think of other issues that could have influenced subject performance.

This experiment must rank as one of the most interesting software engineering experiments performed to date.

Socrates 2014 unconference in the UK

I was at the Socrates unconference at the end of last week. An unconference is a conference with no prearranged speakers, the attendees turn up and some of them volunteer to talk about a topic of their choosing on the day. The talks were structured as half a dozen parallel sessions of an hour each in rooms dotted around two different buildings.

I had previously been to half a dozen or so of the London Software Craftsmanship meetups (there is a large overlap in the organizers of the two groups) and thought I had some understanding of how the community went about building software engineering knowledge. At the end of the first day this understanding underwent a major revamp (the arts and craft movement struck me as something of a parallel).

Based on the experience of one meeting I would say that the Socrates’ community approach to achieving the goals laid out in the Manifesto for Software Craftsmanship (as exemplified by those present at unconference) is primarily a social one based on personal experiences and shared experiences communicated through meetings and pair programming (yes, pair programming).

A great deal of pair programming was constantly going on and a person’s recent experience of pairing with somebody-or-other was a perfectly natural topic to bring up in casual conversation. I have never seen this kind of widespread community practice of interaction on a detailed before; I think it is great and I hope it spreads.

I volunteered to talk Friday morning about “When is it worth investing in reducing maintenance costs?” (I now have more data than used in my blog post on the topic). The talk did not go well in the sense that while people appeared to understood the analysis they did not seem to understand why anybody would want to use the decision making approach proposed. I got the same impression from people who asked me about the topic during food breaks (I had given a lightening talk Thursday evening with about half the attendees present).

The argument I made was that improving software is an investment intended to reduce future maintenance activities; like all investments the person making it wants receive a worthwhile return on the risk they are taking. The talk derived a requirement on the investment/benefit ratio needed for a code improvement activity to at least break even.

Now I am not always the world’s greatest communicator, so peoples’ lack of understanding may have been down to poor presentation on my part. But, in the evening, thinking about everything I had seen during the day I realised that my proposal for driving code improvement decisions using an economic model ran counter to the spirit of software craftsmanship as practiced by those present. This is not to say that the software craftsman are anti-economics, but that they want to be proud of their work and require that it meet certain personal and community standards, which may mean being less than economically efficient in some cases. At your average developer conference I would have expected zero interest, but here I had made the mistake of underestimating the strong craft influence and the socially derived approach (rather than trying to use experimental evidence) to finding solutions to software engineering problems.

There were a handful of people at the meeting interested in working towards a scientific approach to obtaining solutions to software engineering problems, i.e., using evidence derived from experiments. At one of the sessions a small group of us talked about how the software craftsman community might help researchers interested in experimental research (perhaps by helping to find professional subjects or by being willing to spend time discussing industry problems). I made my usual appeal for data that could be made public.

I suspect that many software craftsman would be interested in monitoring their own performance and that it would be worthwhile providing pointers to tools and techniques that might be used. Watch this space for progress.

The most interesting session I went to was by Steve Hayes who talked about his experience of starting and running a transparent company (this involves making information that companies usually keep confidential, such as employee, public). I had read about such companies before but this was my first encounter with somebody who had done it in practice.

The event appeared to run itself very smoothly, probably as much due to the invisible hard work of the organizers as much as the more visible attendee work. I would recommend the host venue, Farncombe conference centre, to anyone wanting to run a conference with lots of breakout rooms and social spaces. The food was high quality and artistically presented, demanding that both desserts on the menu be consumed.

Anybody who is in a rush to experience a Socrates unconference can visit Germany in August (a contingent from the UK are already booked).

Recent Comments