Archive

Census of general purpose computers installed in the 1960s

In the 1960s a small number of computer manufacturers sold a relatively small number of general purpose computers (IBM dominated the market). Between 1962 and 1974 the magazine Computers and Automation published a monthly census listing the total number of installed, and unfilled orders for, general purpose computers. A pdf of all the scanned census data is available on Bitsavers.

Over the last 10-years, I have made sporadic attempts to convert the data in this pdf to csv form. The available tools do a passable job of generating text, but the layout of the converted text is often very different from the visible layout presented by a pdf viewer. This difference is caused by the pdf2text tools outputting characters in the order in which they occur within the pdf. For example, if a pdf viewer shows the following text, with numbers showing the relative order of characters within the pdf file:

1 2 6

3 7

4 5 8 |

the output from pdf2text might be one of the four possibilities:

1 2 1 2 1 1

3 3 2 2

4 5 4 3 3

6 5 4 5 4

7 6 6 5

8 7 7 6

8 8 7

8 |

One cause of the difference is the algorithm pdf2text uses to decide whether characters occur on the same line, i.e., do they have the same vertical position on the same page, measured in points ( inch, or ≈ 0.353 mm)?

inch, or ≈ 0.353 mm)?

When a pdf is created by an application, characters on the same visual line usually have the same vertical position, and the extracted output follows a regular pattern. It’s just a matter of moving characters to the appropriate columns (editor macros to the rescue). Missing table entries complicate the process.

The computer census data comes from scanned magazines, and the vertical positions of characters on the same visual line are every so slightly different. This vertical variation effectively causes pdf2text to output the discrete character sequences on a variety of different lines.

A more sophisticated line assignment algorithm is needed. For instance, given the x/y position of each discrete character sequence, a fuzzy matching algorithm could assign the most likely row and column to each sequence.

The mupdf tool has an option to generate html, and this html contains the page/row/column values for each discrete character sequence, and it is possible to use this information to form reasonably laid out text. Unfortunately, the text on the scanned pages is not crisply sharp and mupdf produces o instead of 0, and l not 1, on a regular basis; too often for me to be interested in manually correctly the output.

Tesseract is the ocr tool of choice for many, and it supports the output of bounding box information. Unfortunately, running this software regularly causes my Linux based desktop to reboot.

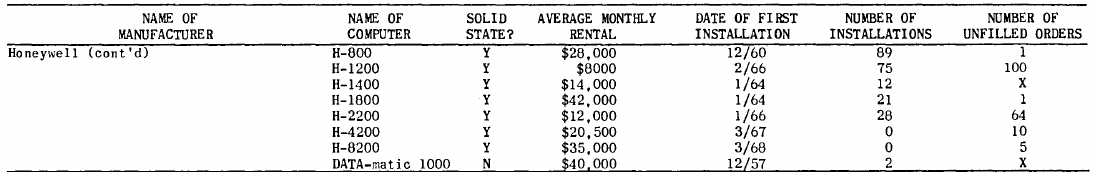

I recently learned about Amazon’s Textract service, and tried it out. The results were impressive. Textract doesn’t just map characters to their position on the visible page, it is capable of joining multiple rows within a column and will insert empty strings if a column/row does not contain any characters. For instance, in the following image of the top of a page:

the column names are converted to "NAME OF MANUFACTURER","NAME OF COMPUTER", etc., and the empty first column/row are mapped to "".

The conversion is not quiet 100% accurate, but then the input is not 100% accurate; a few black smudges are treated as a single-quote or decimal point, and comma is sometimes treated as a fullstop. There were around 20 such mistakes in 11,000+ rows of numbers/names. There were six instances where two lines were merged into a single row, when the lines should have each been a separate row.

Having an essentially accurate conversion to csv available, does not remove the need for data cleaning. The image above contains two examples of entries that need to be corrected: the first column specifies that it is a continuation of a column on the previous page (over 12 different abbreviated forms of continued are used) Honeywell (cont'd) -> Honeywell, and other pages use a slightly different name for a particular computer DATA-matic 1000 -> Datamatic 1000. There are 350+ cleaning edits in my awk script that catch most issues (code+data).

How useful is this data?

Early computer census data in csv form is very rare, and now lots of it is available. My immediate use is completing a long-standing dataset conversion.

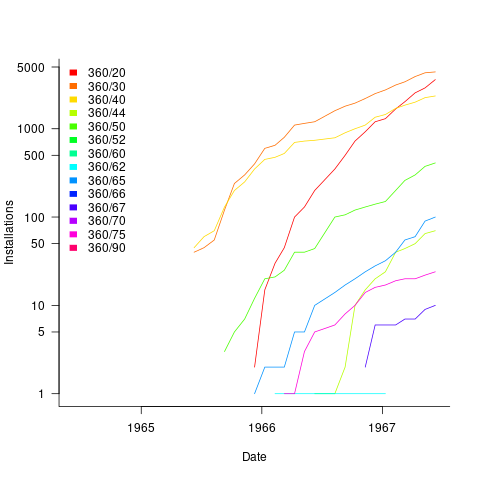

Obtaining the level of detail in this census, on a monthly basis, requires some degree of cooperation from the manufacturer. June 1967 appears to be the last time that IBM supplied detailed information, and later IBM census entries are listed as round estimates (and only for a few models).

The plot below shows the growth in the number of IBM 360 installations, for various models (unfilled orders date back to May 1964; code+data):

Unreliable cpus and memory: The end result of Moore’s law?

Where is the evolution of commodity cpu and memory chips going to take its customers? I think the answer is cheap and unreliable products (just like many household appliances are priced low and have a short expected lifetime).

We have had the manufacturer-customer win-win phase of Moore’s law and I think we are now entering the win-loose phase.

The reason chip manufacturers, such as Intel, invest so heavily on continually shrinking dies is the same reason all companies invest, they expect to get a good return on their investment. The cost of processing the wafer from which individual chips are cut is more or less constant, reducing the size of a chip enables more to fitted on the same wafer, giving more product to sell for more or less the same wafer processing cost.

The fact that dies with smaller feature sizes have reduce power consumption and can run at faster clock speeds (up until around 10 years ago) is a secondary benefit to manufacturers (it created a reason for customers to replace what they already owned with a newer product); chip manufacturers would still have gone down the die shrink path if these secondary benefits had not existed, but perhaps at a slower rate. Customers saw, or were marketed, this strinkage story as one of product improvement for their benefit rather than as one of unit cost reduction for Intel’s benefit (Intel is the end-customer facing company that pumped billions into marketing).

Until recently both manufacturer and customer have benefited from die shrinks through faster cpus/lower power consumption and lower unit cost.

A problem that was rarely encountered outside of science fiction a few decades ago is now regularly encountered by all owners of modern computers, cosmic rays (plus more local source of ‘rays’) altering the behavior of running programs (4 GB of RAM is likely to experience a single bit-flip once every 33 hours of operation). As die shrink continues this problem will get worse. Another problem with ever smaller transistors is their decreasing mean time to failure (very technical details); we have seen expected chip lifetimes drop from 10 years to 7 and now less and decreasing.

Decreasing chip lifetimes is actually good for the manufacturer, it creates a reason for customers to buy a new product. Buying a new computer every 2-3 years has been accepted practice for many years (because the new ones were much better). Are we, the customer, in danger of being led to continue with this ‘accepted practice’ (because computers reliability is poor)?

Surely it is to the customer’s advantage to not buy devices that contain chips with even smaller features? Is it only the manufacturer that will obtain a worthwhile benefit from future die shrinks?

Recent Comments