Patterns of regular expression usage: duplicate regexs

Regular expressions are widely used, but until recently they were rarely studied empirically (i.e., just theory research).

This week I discovered two groups studying regular expression usage in source code. The VTSBULeeLab has various papers analysing 500K distinct regular expressions, from programs written in eight languages and StackOverflow; Carl Chapman and Peipei Wang have been looking at testing of regular expressions, and also ran an interesting experiment (I will write about this when I have decoded the data).

Regular expressions are interesting, in that their use is likely to be purely driven by an application requirement; the use of an integer literals may be driven by internal housekeeping requirements. The number of times the same regular expression appears in source code provides an insight (I claim) into the number of times different programs are having to solve the same application problem.

The data made available by the VTSBULeeLab group provides lots of information about each distinct regular expression, but not a count of occurrences in source. My email request for count data received a reply from James Davis within the hour 🙂

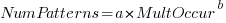

The plot below (code+data; crates.io has not been included because the number of regexs extracted is much smaller than the other repos) shows the number of unique patterns (y-axis) against the number of identical occurrences of each unique pattern (x-axis), e.g., far left shows number of distinct patterns that occurred once, then the number of distinct patterns that each occur twice, etc; colors show the repositories (language) from which the source was obtained (to extract the regexs), and lines are fitted regression models of the form:  , where:

, where:  is driven by the total amount of source processed and the frequency of occurrence of regexs in source, and

is driven by the total amount of source processed and the frequency of occurrence of regexs in source, and  is the rate at which duplicates occur.

is the rate at which duplicates occur.

So most patterns occur once, and a few patterns occur lots of times (there is a long tail off to the unplotted right).

The following table shows values of  for the various repositories (languages):

for the various repositories (languages):

StackOverflow cpan godoc maven npm packagist pypi rubygems

-1.8 -2.5 -2.5 -2.4 -1.9 -2.6 -2.7 -2.4 |

The lower (i.e., closer to zero) the value of  , the more often the same regex will appear.

, the more often the same regex will appear.

The values are in the region of -2.5, with two exceptions; why might StackOverflow and npm be different? I can imagine lots of duplicates on StackOverflow, but npm (I’m not really familiar with this package ecosystem).

I am pleased to see such good regression fits, and close power law exponents (I would have been happy with an exponential fit, or any other equation; I am interested in a consistent pattern across languages, not the pattern itself).

Some of the code is likely to be cloned, i.e., cut-and-pasted from a function in another package/program. Copy rates as high as 70% have been found. In this case, I don’t think cloned code matters. If a particular regex is needed, what difference does it make whether the code was cloned or written from scratch?

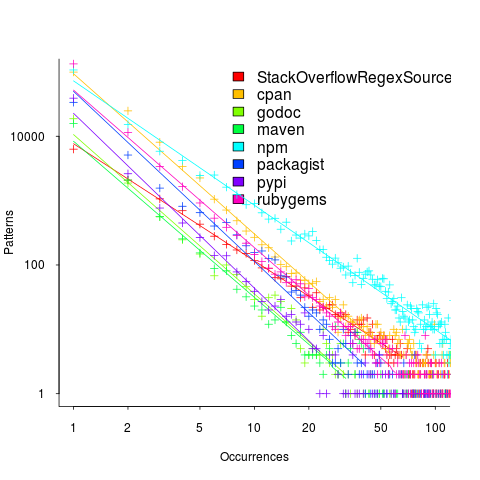

If the same regex appears in source because of the same application requirement, the number of reuses should be correlated across languages (unless different languages are being used to solve different kinds of problems). The plot below shows the correlation between number of occurrences of distinct regexs, for each pair of languages (or rather repos for particular languages; top left is StackOverflow).

Why is there a mix of strong and weakly correlated pairs? Is it because similar application problems tend to be solved using different languages? Or perhaps there are different habits for cut-and-pasted source for developers using different repositories (which will cause some patterns to occur more often, but not others, and have an impact on correlation but not the regression fit).

There are a lot of other interesting things that can be done with this data, when connected to the results of the analysis of distinct regexs, but these look like hard work, and I have a book to finish.

Hello Derek,

One explanation for the repetition you can see in our data is that regexes are commonly applied to process common inputs — e.g. emails, URLs, file paths, etc. See also: [1].

An alternative explanation is that the regex extraction methodology we followed could be biased by engineering practices. In particular, that regex corpus was obtained by statically extracting regexes from files in GitHub projects. If software engineers conducted wholesale file duplication and pasted file F into repositories X, Y, and Z, we would count all regexes in F three times. Although the regex would indeed be used in each of those repositories, I would hesitate to call this “regex re-use”. See also: [2].

You wrote “In this case, I don’t think cloned code matters. If a particular regex is needed, what difference does it make whether the code was cloned or written from scratch?”. This is a good question! We considered the risks of cross-language regex re-use in another paper. See [3] for a mix of qualitative and quantitative work on this.

For software engineers’ perspectives on regexes, you might enjoy [4].

Abridged versions of the papers I referenced can be found on my Medium blog [5].

Regards,

James

[1] See our sketch-estimates in Table 3 of http://people.cs.vt.edu/davisjam/downloads/publications/DavisCoghlanServantLee-EcosystemREDOS-ESECFSE18.pdf.

[2] See “Threats to Validity — Construct validity” in http://people.cs.vt.edu/davisjam/downloads/publications/DavisMichaelCoghlanServantLee-LinguaFranca-ESECFSE19.pdf

[3] The potential risks of cross-language regex re-use: http://people.cs.vt.edu/davisjam/downloads/publications/DavisMichaelCoghlanServantLee-LinguaFranca-ESECFSE19.pdf

[4] Qualitative work on engineering practices surrounding regexes: http://people.cs.vt.edu/davisjam/downloads/publications/MichaelDonohueDavisLeeServant-RegexesAreHard-ASE19.pdf

[5] Abridged write-ups of research papers: https://medium.com/@davisjam

@James Davis

Another prompt reply!

The regex extraction methodology might be biased towards particular domains (it is in that open source tends to target what developers consider to be interesting,e.g., there are lots of implementations of C compilers, but Cobol compilers are rarely implemented). But if a pattern of use exists in a subset of domains, it’s a good indicator that a similar pattern will exist in other domains.

Copying of files from another project is only an issue if the copied regex is in dead code, i.e., code that was only copied because it happened to be in the same file containing the desired functionality. In this case the regex would not have been created if the developer had written code from scratch.

I suspect there will be other associations between regex characteristics and frequency of use, and a fishing expedition will probably find something. The question is, what does it all mean and why might it be useful? I have no good (or even not so good) answer to this.

Re: [4]. I am somewhat anti-surveys. So many software engineering surveys are convenience samples and rather bland, i.e., nothing is learned from them. Chapman and Wang ran an interesting experiment, and I think there is lots to learn from this.

Looking forward to reading your next paper.

@Derek Jones

> I suspect there will be other associations between regex characteristics and frequency of use, and a fishing expedition will probably find something. The question is, what does it all mean and why might it be useful? I have no good (or even not so good) answer to this.

From a REDOS perspective, I think the most interesting aspect of frequency of use is not on a per-regex basis but rather on the basis of regex feature usage. Are most regexes “regular”, i.e. Kleene regular expressions, or do they use extended features that are difficult/impossible to support in linear time? See for example Russ Cox’s RE2 engine [1], though the “Lingua Franca” questions I have raised make me wonder how risky it is to port to. Memoization offers an alternative and more backwards-compatible approach [2].

> RE: [4]. I am somewhat anti-surveys. So many software engineering surveys are convenience samples and rather bland, i.e., nothing is learned from them.

Fair enough. I think you get more mileage from mixed-methods work (e.g. surveys + interviews). I believe we learned plenty that wasn’t previously in the literature about regex practices, though.

====

[1] Introduced in the widely-circulated article “Regular Expression Matching Can Be…” https://swtch.com/~rsc/regexp/regexp1.html

[2] My sketch of a memoization approach similar to the one in Perl: http://people.cs.vt.edu/davisjam/downloads/publications/Davis-RethinkingRegexEngines-ESECFSE19SRC.pdf

@James Davis

We are coming at the data from different directions. You are obviously interested in regexs from the implementation and use perspective. My interest is in what the usage tells us about application requirements and developer habits.

> Re:[1] table 3.

Yes, a few regexs are used a lot. But why do so many appear twice, and not so many three times, etc? And, what’s the explanation for the -2.5 power law exponent? Is this being driven by something completely unconnected with regexs (perhaps the likelihood that a file containing a regex is copied, but the code around the regex is unused; no, that would produce an exponential distribution)?

One explanation of the regex occurrence I would like to point out is the length of the regular expressions. There are simple regexes with only frequently used regular expression features. They are short, easy to understand, and probably also easy to come up with.

Examples of those are \d+, \d*, [a-z]+, [a-zA-Z], etc.

If you want to match strings consisted of only characters and digits, there is a high chance you write it as [a-zA-Z0-9]+ or \w+.

In this regard, you might also be interested in another Carl’s paper: “Exploring Regular Expression Usage and Context in Python” at https://kstolee.github.io/papers/ISSTA2016.pdf